What do they eat? For killer whales, the answer is....practically everything. That makes it sound like they'll eat anything, and they will, but not always willingly. Orcas in different parts of the world eat different things, and that's all they eat. The obvious example of particular eating is the residents (salmon-eaters) and transients (mammal-eaters) of BC. But orcas in other parts of the world are also specialized eaters, and this is what makes them unique. Since other countries haven't studied orcas as extensively as BC, much of what we know of orcas around the world has come from their diet. This page will explore the hunting methods employed by orcas around the world, and some of their prey.

This is the killer whale at its deadliest and, in some cases, most magnificent. Their hunting techniques are so outrageous, so amazing, and often so intelligent they boggle the mind. But watching them hunt, even in photos, can bring back the old fear humans used to harbour for these amazing creatures. If nothing else, it should make you give them a lot of respect. This is the orca at its most raw and brutal moment-the moment of the kill. Not to be mistaken for the most important moment of course, but certainly the bluntest.

WARNING: Some of these photos might be considered graphic. Orca hunts can get pretty violent, and that's what these pictures are of.

Salmon

Salmon is at the heart of BC's coastal ecosystem. They are also the heart of a resident orca's diet. Resident orcas eat mostly salmon, though they'll feed on smaller and deeper-dwelling fish if they have to. They LOVE salmon. 96% of fish eaten during spring-fall are salmon. They seem to like Chinook salmon the best, because chinooks make up 65% of the salmon observed being eaten. When foraging for salmon, residents typically spread out and move across the area in a way that looks like they're sweeping the area for salmon. They stay in constant vocal contact, and use echolocation to locate the unlucky fish. Fish are generally eaten individually, though sometimes a mother and calf shares a salmon. Orcas who eat salmon (BC residents) also eat squid, lingcod, halibut, and other types of similar fish.

Above: A Southern Resident in BC with a half-eaten salmon, scanned from Killer Whales by John Ford, Graeme Ellis and Kenneth Balcomb.

Large Whales

Orcas around the world have dined on large whales. In fact, its this prey which gave them the name Killer Whales. Whalers saw a pod of orcas attacking and eventually killing a large baleen whale, and called them 'whale killers'. Somewhere along the way, someone messed up the translation and they ended up being called Killer Whales. There are many species of whales that orcas attack and kill. In Mexico, there was a very well-documented case of orcas attacking and nearly killing a blue whale, the largest animal on earth. Minke whales are often seen being killed by orcas in BC. Fin whale killings are also sometimes seen in BC, as are humpbacks. Killer whales prey on grey whales in California so often I gave them their own section (see below). Other whales attacked are: bowhead whales, sei whales, and right whales. The orcas also are daring enough to attack the powerful sperm whale, occasionally succeeding in taking one down. In other words, pretty much all of the great whales have been eaten by orcas. They are known for their exclusive tastes; when orcas take down a great whale, they take off the lips, and especially the tongue, which seems to be a sort of delicacy. Sometimes that's all they take; other times they take as much as they can before the whale sinks. This preying on baleen whales, in fact, earned the orcas a friendship with-of all people-whalers in a certain Australia bay:

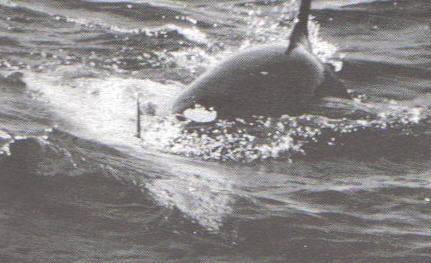

Above: A minke whale is attacked by transient orcas off Vancouver Island, BC, scanned from National Georgraphic, the April 2005 edition.

Below: A group of orcas attack a mighty sperm whale (the big tail in the middle), scanned from the Blackfish Sounder, issue 6.

Porpoises

Porpoises are fast little buggers. They're hard to catch-but they put up a lot less of a fight than sea lions. Which is probably why BC transients like them. Both Dall's Porpoises and Harbour Porpoises are targeted; not only in BC but most often there. Dall's porpoises, being more abundant, are often the victim of transients' attacks, as well as their 'games'. Porpoises are hard to catch, because they're faster than orcas; to get around this little problem, transients trade off the chase. One whale will chase the porpoise, then that whale will stop and another one will pick it up. A little porpoise is no match for the orca's cooperative hunting, though sometimes their speed does help them get away. One caught, orcas will propel the porpoise out of the water, throwing them in the air and hitting them with their tails. Transients can strip a porpoise down in less than two minutes, leaving nothing but the skin or the lungs behind. Contrary to the transients, Dall's porpoises have been seen swimming peacefully WITH residents. In fact, one Alaskan pod of orcas played host to a Dall's porpoise, which swam with them for nearly a year. However, residents aren't always so gentle with porpoises. They have occasionally been seen harassing the little cetaceans, though they'll never eat them. The most notable instance of this is the A36 incident, when the three brothers harassed a porpoise for quite a while, before letting it go, apparently unharmed.

Above: A North-Pacific transient knocks a Dall's porpoise out of the water during a dramatic hunt, scanned from the book A Catalogue of Prince William Sound Killer Whales.

Below: An Alaskan transient shoots a Dall's Porpoise into the air, scanned from the book Marine Mammals of the World, a National Audubon Society book.

Sharks

JAWS promoted the idea that Great White Sharks (which don't really look that much like the one in JAWS, which was mechanical and much bigger than normal great whites...hey, its Hollywood!) were the master predator in the sea. Ruling king of the oceans. No one messed with these guys. Right? WRONG! Orcas are the top predator in the ocean, and their reach even extends to the few deer they pluck off when the deer swim from island to island. Just proving the fact that orcas reign over sharks, a great white was killed by an orca around 1998. 30 km west of San Francisco, near the Farallon Islands, a nature cruise headed out to find 2 orcas that had been spotted earlier. They found the whales-and a 3-4 metre shark as well. Most scientists presumed sharks and orcas, as top predators, ignored each other. But suddenly, one orca charged at the shark underwater, then surfacing with the dead creature and parading around with it for the next 15 minutes. Maybe she was trying to prove that orcas really are the top predator! After that, she (who was later identified as CA2) and her companion began to eat the shark. Similarly, in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, a group of orcas killed and ate a Mako shark, something never seen before. Sharks are actually quite important to an orca's diet in New Zealand, as are sting rays, which they sometimes use as frisbees!

Above: An orca, probably CA2, shows off the great white shark in its jaws, scanned from the Blackfish Sounder, issue 6.

Below: Orcas eye a Mako shark, which they later killed and ate, in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. This photo from the April 2005 National Geographic issue.

Hunting on the Beach (In Patagonia)

Its one of the most dramatic, exciting, and well-known styles of hunting orcas use. The stategy that gets on tv and in books-a difficult and dangerous manoeuvre. And it only happens 1, maybe 2 places in the world. Stranding on purpose.

The best-known place for this type of hunting is Patagonia, Argentina. There, a specific type of orca (despite popular belief, not ALL orcas in Argentina hunt this way) has a very special way of hunting. An orca will patrol up and down the beach where all the sea lions are hauled out. Pups play in the breakers, vulnerable and slow. When the orca sees its chance, it charges up onto the beach, erupting from the water onto the sand in a dramatic explosion of spray, snapping the pup into its mouth. The poor little sea lion's horrifying adventure doesn't end there though. The Patagonian orcas enjoy playing games with the little creatures, throwing them in the air, and most impressively, hitting them so hard with their tails the pups fly into the air. This amazing stategy is very tricky and is treated with caution-females do it mostly, since males, being much bigger, could get stranded for good. And its not fool-proof; some orcas DO end up trapped. Its taught very carefully to the youngsters. The orca doing the attacking with charge up the beach with the calf a little farther back. Once the orca catches a sea lion, it throws the pup back to the calf. Most of the time, one orca will get a pup, or even a fully-grown sea lion, and take it back to the family in deeper water. They also take elephant seals. This takes lots of practice to perfect, and often, Patagonia orcas will hunt with other, safer ways.

Above: A massive bull orca charges up the beach to catch a sea lion pup-not the one fleeing for its life in the photo, but another one unseen under water. Scanned from Killer Whales by Mark Carwadine.

For more beach-hunting photos, go HERE

Hunting on the Beach (in the Crozet Islands)

There are two places in the world you can see the magnificent and slightly terrifying display of power described above. Above, it was about Patagonia, Argentina. The other place in the world is the Crozet Islands. Here, the orcas target sea lions, and...penguins. The sea lion pups, after they outgrow their mothers and the mothers leave, play in the surf and on the beach until instinct calls them to the water. Its rather pathetic-they see the orcas, but they don't understand what it means. Until the orcas charge out of nowhere and eat them. Here, the Crozet orcas use the beach for a lot of things. Once, an attack on a Minke whale calf escaladed to the calf throwing itself on the beach. The orcas simply went up on the beach, grabbed it, and pulled it back into the water, stripping it down to a skeleton in 25 minutes. Clearly, Crozet orcas aren't to messed with. There are about 100 Crozet orcas who use the beach-technique. They teach it to their calves as well. Juvenile orcas are lined up parallel to the beach, and the other orcas push it up to the beach until the youngster wiggles away into deeper water. Then they repeat.

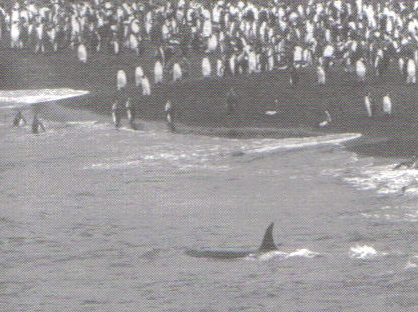

Above: A Crozet orca eyes some penguins while the penguins warily eye the orca, scanned from the Blackfish Sounder, issue 7.

Below: A lone orca patrols the beach while penguins watch anxiously, scanned from Killer Whales by Mark Carwadine.

Grey Whales Off California

Off California, migrating grey whale mothers have to be especially careful. Orcas there have developed a taste for their calves. While this occasionally happens off Washington and BC, and probably other places, it most often happens off California. The grey whales are especially venerable there, bringing all their newborn calves along the same route. A route the orcas have learned to trace over time. The orcas go to practically any length to get the calves. They do their best to first seperate the calves from their mothers, then drown the calf and feast. However, the whales do practically anything to protect their babies, as well. One grey whale mother placed her calf on her stomach, rolled over, and arched her back so that the baby was out of the water! Eventually the orcas gave up, left, and the two grey whales triumphantly continued on.

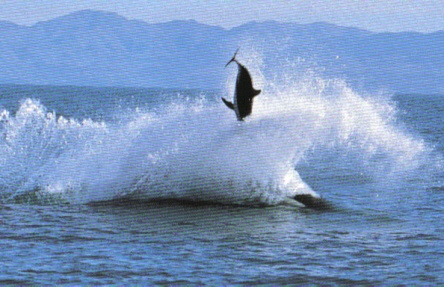

Above: A transient off California leaping on a grey whale calf to drown it, from The Blackfish Sounder, issue 10.

More photos of attacks on Californian grey whales HERE

Dolphins and Other Small Whales

In many parts of the world, dolphins play a large part in the orca's diet. Pacific White-Sided Dolphins in BC have a two-sided relationship with orcas. Pacific White-Sideds, or lags, often travel and bow-ride along the wake of the resident orcas, jumping around them, stealing scraps when they hunt the salmon, and sometimes driving them nuts. However, when the BC transients show up, the dolphins practically disappear. As illustrated in the photo above, transients aren't so friendly with the playful creatures. Orcas also take the rarer beaked whales in deeper waters, but because of the rareness of the beaked whales, we don't have positive information about it. Since orcas inhabit every ocean, practically all (oceanic)dolphins have reason to fear them. Dusky dolphins are taken off New Zealand's coast, bottlenose dolphins are taken from practically everywhere...you get the picture. Other small whales are also taken by orcas. In the far north, belugas and narwhals have been preyed upon, though not as frequently as seals, and in open ocean, pilot whales and bottlenose whales are taken. Typically, the orcas will rope one whale off from its pod and chase it until it tires out or they do. Then they ram it with their heads or tails, sometimes thrusting it out of the water, and its all over.

Above: A BC transient (unseen behind the spray) tosses a Pacific White-Sided Dolphin into the air near Port Hardy, from the Blackfish Sounder issue 7.

Below: Off Kaikoura, New Zealand, a dusky dolphin is rammed into the air, scanned from Killer Whales by Mark Carwadine.

Above: Three orcas spyhop around a vulnerable-looking Ross seal, from the book Killer Whales by Mark Carwadine.

Below: A group of orcas spyhopping around a rather unfortunate Weddell Seal, while a Leopard Seal looks on, from Issue 13 of the Blackfish Sounder.

Herding Herring In Norway

Another remarkable hunting technique hails from Norway. Off the Norwegian coast, the resident (not resident like fish-eating, resident like they live there) orcas prey off the huge schools of herring that pass by. The pods have elaborate strategies and movements that they use to herd the schools into a tight ball. Then they use more methods to control the herring while individual whales smack the fish with their tails. The stunned fish float out of the massive ball of herring, and the whales eat them.

Above: A Norwegian whale herding herring, from Killer Whales of the World by Robin Baird.

Sea Lions

Sea lions are very popular prey for orcas-but they're also almost just as vicious in a fight as the transients that eat them. Of course, I'm taking about Stellar Sea Lions here-big, strong, and clawed. It takes a whole pod of orcas to take down one of these guys-and the orcas have the scars to prove it. No matter how big the fight, though, the sea lions still often go down. Harbour seals are often targeted (they put up less of a fight), and many other pinnipeds as well.

Above: The T7 BC transient family attacking a sea lion; one orca is tail-slapping with the sea lion, scanned from Transients by John Ford and Graeme Ellis.

Birds

Photo of juvenile transient orca charging a bird

Birds aren't actually prey of the BC transients-as far as we can tell, they're practice tools...or toys! Birds, often rhinocerous auklets or common murres. Other victims have included black brant ducks, cormorants, western grebes, surf scoters, and even common loons! Usually, it's the juvenile transients who do this-attacking the bird and, usually, letting it escape or leaving it to die. Once in a while, they eat the bird, but usually they seem to use their winged victims for playtime and practice for the bigger prey.

Stingrays

Photo of Orca Hunting Stingray

In New Zealand, orcas have developed a unique way to play with their favourite treat. While the orcas there also eat blue sharks and penguins, their favourite delicacy is stingrays. And boy, do they enjoy them! Then dig up and flush out the stringrays from the sandy bottom, then grab them and flip them in the air. They then toss them like frisbees to close by whales, and commence a toss-the-stingray-around game with other whales. Later, the stingray is ripped up and eaten.

Above: A New Zealand orca with a tasty stingray, from Issue 8 of the Blackfish Sounder.