But history was happening outside the tank, too. What was going on in the wild, you ask?

Well, in 1973, the Government of Canada began to get concerned about the number of orcas being taken from their waters. They realized that no one really knew how many orcas there were out there, or, to tell the truth, what the heck the orcas were doing. Most of what we knew had come from studying how they ate, not the rest of how they lived. Who'd want to, anyway? These were vicious creatures-teddy bears in captivity, sure, but in the WILD? You'd be crazy to study them!

Ok so I'm exaggerating a bit. But there's no denying people were afraid of the very idea. A few people, however, decided to be different...these people would become some of the foremost experts on killer whales in the world. And a lot of these people, we have to thank the captive industry for.

This page will introduce some of the researchers who have caused the most insight into the orca's life. Note, that this is mostly in BC. Researchers in other countries, like the Russia Project and Ingrid Visser, will be included on the next page.

One of the first researchers to start with orcas was Graeme Ellis, co-author of the ID book, Killer Whales. Graeme Ellis worked with Bob Hunter, owner of Sealand, capturing and training whales for the aquarium. He was involved with the rare white whale Chimo's capture, and was angry at the lack of interest in the Scarredjaw Cow's fate.

The first orca he had to train was a male named Irving, who was kept at Pender Harbour for about four months before he escaped. A big male from A5 pod probably, Ellis was, understandably, scared of the orca. He was trying to get Irving to eat. The two established trust through a splashing game, and that's what made Irving eat, giving Ellis food for thought.

While Ellis quickly became one of the few people who actually knew quite a bit about orcas at the time, taking out other researchers and actually diving with the whales, another person was setting up camp-literally-off Johnstone Strait.

Paul Spong started out doing tests on a captive whale named Skana, at the Vancouver Aquarium, trying to determine her intelligence. Skana got most of them right, and eventually got a hang of the test. And then something bizarre happened-Skana systematically got every answer wrong! Spong was astonished. The whale was bored!

Skana proved she wasn't just a dumb animal. One time, when Spong was sitting with his feet in the water, Skana rushed over and raked her teeth over his feet. Startled and understandably freaked out, Spong yanked his feet away. Skana cruised away and Spong decided to put his feet back in. Again, Skana charged and raked her teeth over the feet, not hurting him but scaring him. About ten more times they did this, until finally Spong left his feet in while Skana did it. After that, she stopped. She had been training him!

A similar incident of an orca deconditioning a human of fear was when Graeme Ellis was working with Irving. Ellis' incident was a bit more disturbing-he dove in to feed the orca, and Irving charged up to his face and snapped his jaws right in front of him! Like Spong, Ellis got out of there, FAST. But for some unknown reason, he got back in. Like Skana, Irving continued until Ellis didn't flinch. Then the big whale was calm and friendly!

Paul Spong, meanwhile, became a loud voice for Greenpeace, speaking out against whaling and captive orcas. He moved his family to Hanson Island in Johnstone Strait, where he set up a research station called OrcaLab. Setting up cameras underwater and above surface, and setting up hydrophones (underwater microphones) throughout the area, Spong would later send the live feed of the BC orcas to people around the world, VIA the internet. Today, by going to Orca-Live, you can watch live feed of orcas in Johnstone Strait, read the updates telling you which orcas you're watching, and chat with other orca-lovers, while listening to the calls of the BC orcas.

Stubbs became the first identified whale, known as A1. The pods began to be arranged by letters, and whales by numbers. Relations were figured out; it was an exciting time to be a whale researcher. John Ford, who had become an expert at figuring out the different dialects of the different pods, began to analyse sound recordings of captures, figuring out which captive orcas came from which pods. Moby Doll, for instance, almost certainly came from J pod, because the J pod dialect has remained unchanged for years.

Speaking of the J pod, while everyone tried to figure out the northern whales, Kenneth Balcomb and a team of researchers headed down to the San Juan Islands. Setting up the Center for Whale Research, they began their own survey down south, finding three pods entirely separate from the northern whales, yet like them in almost every way.

Three types of whales emerged. Northern and Southern residents, fish-eating whales with close family bonds who never interacted with the other community, and transients, wandering, mammal-eating whales with mysterious ways and less stronge familial bonds.

It wasn't easy. The A-pod, for example, took many years. There was a pod known as the Six, who were very confusing. No one could figure out if they were part of Stubb's pod, or Top Notch's, or what. Finally, Dr. Bigg 'cleaned up the As', and established 'The Six' as a third A-pod, the A4 pod. The transients would take many more years.

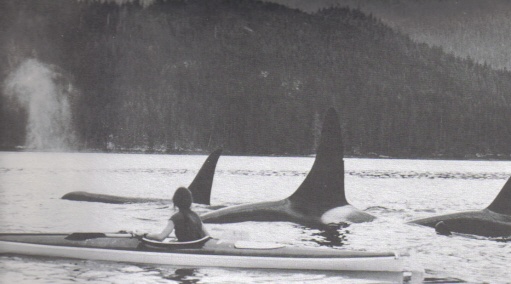

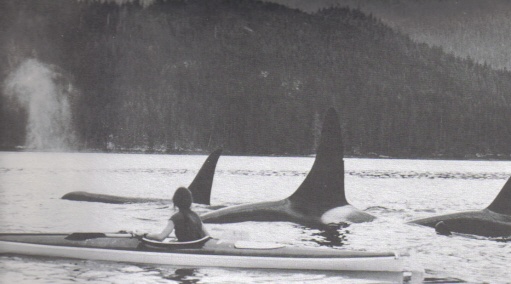

Alexandra Morton arrived on the scene right about now. After studying two captive whales in California (Orky2 and the infamous Corky2, actually), Alex headed out to BC. Jumping right into the fray of researchers, photographers and scientists, Alex met her husband, Robin Morton, who was investigating the Rubbing Beaches at Robson Bight.

Robin Morton, along with many other people, had begun to unravel the mystery of the Rubbing Beaches. Pebble beaches that the northern residents loved to use as a massage parlor, they were an amazing thing to behold.

Alex and Robin Morton became an excellent team. Sadly, Robin died while diving and filming the whales. A sad loss for the whales and the rest of the world.

Alex came back into the researching world soon after and began to switch her focus to the elusive transients. Soon after, she began to research the effects of loud 'seal-scarers' and salmon farming in the area. Her findings horrified her-the whales were being driven out! Alex became a voice against the invasive salmon farms, seal-scarers, and other threats to the precious eco-system the orcas inhabit.

Soon, another type of orca emerged on the scene-a type even more elusive than the transients! (Just to make life difficult!) The offshores, traveling in huge groups and sounding a lot like residents, are a vastly unknown group of orcas which are being tentatively but eagerly IDed as we speak.